Why primary reform took a hit in 2024

Nonpartisan primaries & instant runoff elections have become much more partisan in recent years

One of the striking trends from last month’s elections was that some versions of election reform — including a blend of nonpartisan primaries, runoff elections, and ranked-choice (RCV, or instant runoff) elections — lost almost everywhere they were on the ballot. These are usually fairly popular reforms, and many of them looked likely to pass earlier in the fall. Why did they fail? In some ways, the best answer is that election reform has become more partisan in recent years. (I took part in a recent Brookings panel discussion on this topic, which can be viewed here.)

Just to review, there were combinations of nonpartisan primaries with top-two, top-four, and top-five RCV runoff elections on the ballot in Arizona, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, South Dakota, and Washington, DC in November. It lost in every one of those places except DC. The current top-four RCV system in Alaska just barely survived a repeal effort, and Missouri passed an initiative to prevent such a system from ever being adopted.

Now, there are plenty of state-specific reasons these reforms went down. This very helpful Brookings report by Darrell West looks at some election results and exit poll data and finds that voters were confused by the initiatives in some states. In others, opposing groups put up rival initiatives, and voters voted down both of them. There was some chicanery involved here and there, and very large spending opposed to the measures in some states. But the fact that these measures failed so broadly suggests a more national answer.

These sorts of election reforms aren’t usually in the news much, but they have been in the past few years for a few very specific reasons:

New York City’s 2021 mayoral race was conducted under RCV rules. Quite a few other cities (including San Francisco and Oakland) use RCV for their elections, but New York City is basically the only city that reliably gets national news coverage. And it was kind of a messy election that produced a pretty clownish and corrupt mayor.

Alaska famously held a top-four RCV congressional election in 2022, and it resulted in Democrat Mary Peltola winning in that conservative state over two high-profile Republicans. Republicans have been angry at that election system ever since.

Partially as a consequence of the Alaska election, Donald Trump has made a point of opposing RCV, which he describes as “ranked choice voting crap” and a “rigged deal.” As a result of that, Trump and his MAGA allies funded anti-RCV campaigns in several states this year. An anti-RCV campaign mailer in Montana argued, “They have OPEN BORDERS. They want OPEN BATHROOMS. They need OPEN PRIMARIES,” effectively tying election reform to everything else Republicans accuse the left of.

The consequences of all this have been to make these types of progressive election reforms much more tied to the Democratic Party. To be sure, such initiatives have generally been more popular among Democrats than Republicans, but they’ve often passed with some Republican support.

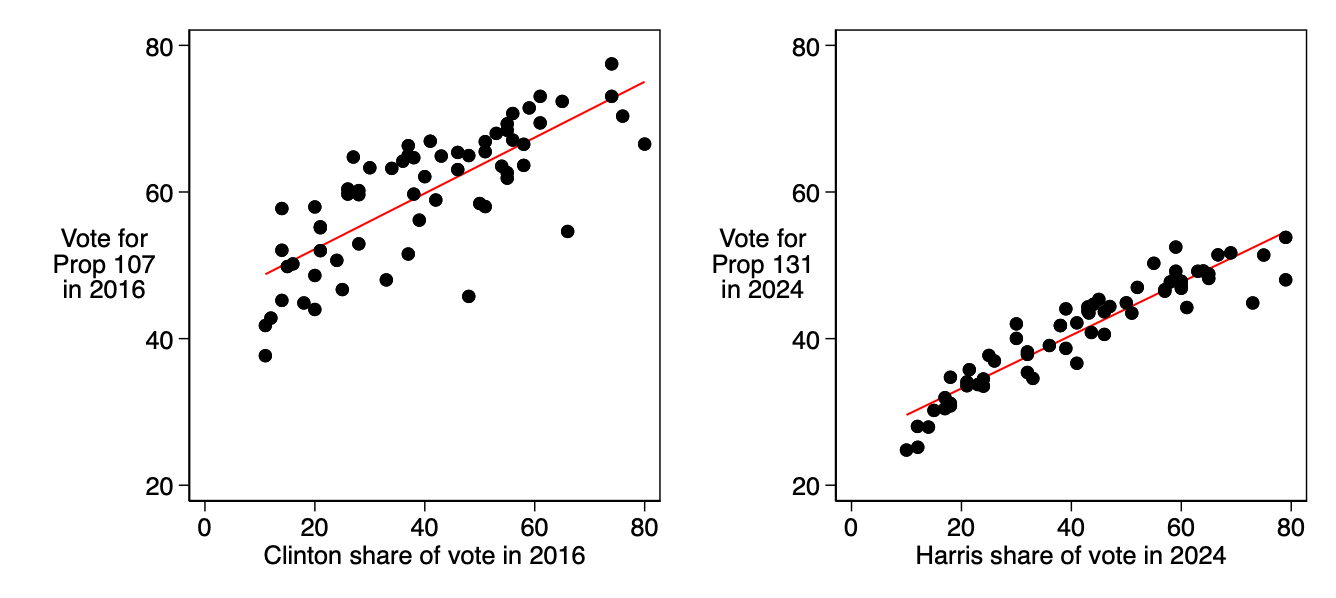

Here’s an example from Colorado. In 2016, Coloradans passed Proposition 107, which created the state’s current system of semi-closed elections that allows independents to participate in either party’s vote-by-mail primary elections. That initiative passed with 56% of the vote; Hillary Clinton got 53% of the vote in the state. That is, the voting reform was more popular than the Democratic presidential candidate, and it passed with some Republican support.

Contrast that with the state’s Proposition 131 this year, which would have created a nonpartisan primary with a top-four RCV runoff. That received 46% of the vote; Kamala Harris got 56% in the state, out-performing reform by ten points.

Donald Trump won 42 Colorado counties in 2016. In those counties, Proposition 107 won in 31 counties and lost in the other 11. Trump won in 41 Colorado counties in 2024. Proposition 131 lost in every one of those counties.

Here’s another way to look at it. Below are scatterplots showing the county-level reform votes and the presidential votes in Colorado in 2016 (left) and 2024 (right). Note how the data are much more tightly clustered around the trend line in 2024. In 2016, the correlation coefficient (r) was 0.77. In 2024, it was .94. Votes on election reform are just much more partisan today.

It’s notable that the nonpartisan primary initiative in Washington, DC passed, but it did so with 73% of the vote. Kamala Harris got 90% of the vote there.

Now, this doesn’t mean that this sort of election reform is dead. It’s quite possible, given these losses, that defeating these initiatives will be less of a priority for Republicans and Trump going forward, and it’s plausible this will be a far less nationalized issue in 2026, which will also likely have a more Democratic-leaning electorate than 2024 did.

But clearly election reformers have their work cut out for them as they try to sell their reform to an increasingly skeptical and partisan electorate going forward.

Measure 3 on the Missouri ballot this year completely excludes political parties from the nomination process.

Only the plurality winner in the state’s open primary advances to the general election.

Progressives win!

Even if support for this sort of initiative has become purely partisan there's a huge amount of progress that could be made - not a lot of blue states or cities have RCV yet. Of course maybe passing reforms in already Democratic controlled areas is less interesting or useful...