A polarized and highly partisan political system gets a lot of criticism. But one of the nice features of it is that people often find a home in it one way or another. If there’s an issue you feel strongly about, chances are one of the two major parties has taken a stance roughly along your lines, and you can choose to vote for them if you want. One of the more destabilizing things is when an important issue arises on which the parties are largely aligned — if you disagree with them, there really isn’t a place for you in electoral politics. In that case, one possible outlet is protest.

This is the situation we find ourselves in with regard to the Israel-Gaza War. Support for Israel has remained one of very few high salience issues on which the bulk of Democrats and Republicans have largely agreed, and this has been the case for decades. There are certainly critics of Israel within both parties, and that is a rising voice within the Democratic coalition, in particular. But for the most part, both parties’ leaders have remained staunch supporters.

Biden’s unequivocal rhetoric in defense of Israel after the October 7th attacks stood out as some of the strongest pro-Israel statements by an American president and won him a good deal of praise from Israel supporters. He’s clearly been bothered by Israel’s wildly disproportionate military response and has expressed some strong criticism, but that hasn’t led to any significant changes in U.S. military support. Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, as big an Israel backer as you’ll find in the U.S. Senate, recently issued a strong condemnation of Israel’s behavior during the war. Again, though, this has not really slowed U.S. military support.

There are any number of reasons why this might be the case. Biden is a longstanding Israel supporter, and his views of Israel were shaped at a time when that nation was perceived as a fragile, endangered democracy and a home to Holocaust survivors, rather than the economic and military regional powerhouse it is today.

Biden is also the head of a party coalition that is notably conflicted about this war. The Democratic Party consists of older and more moderate voters who tend to sympathize with Israel (even if they have qualms about Israel’s current actions) and younger, more progressive voters who view Israel as a militaristic apartheid state.

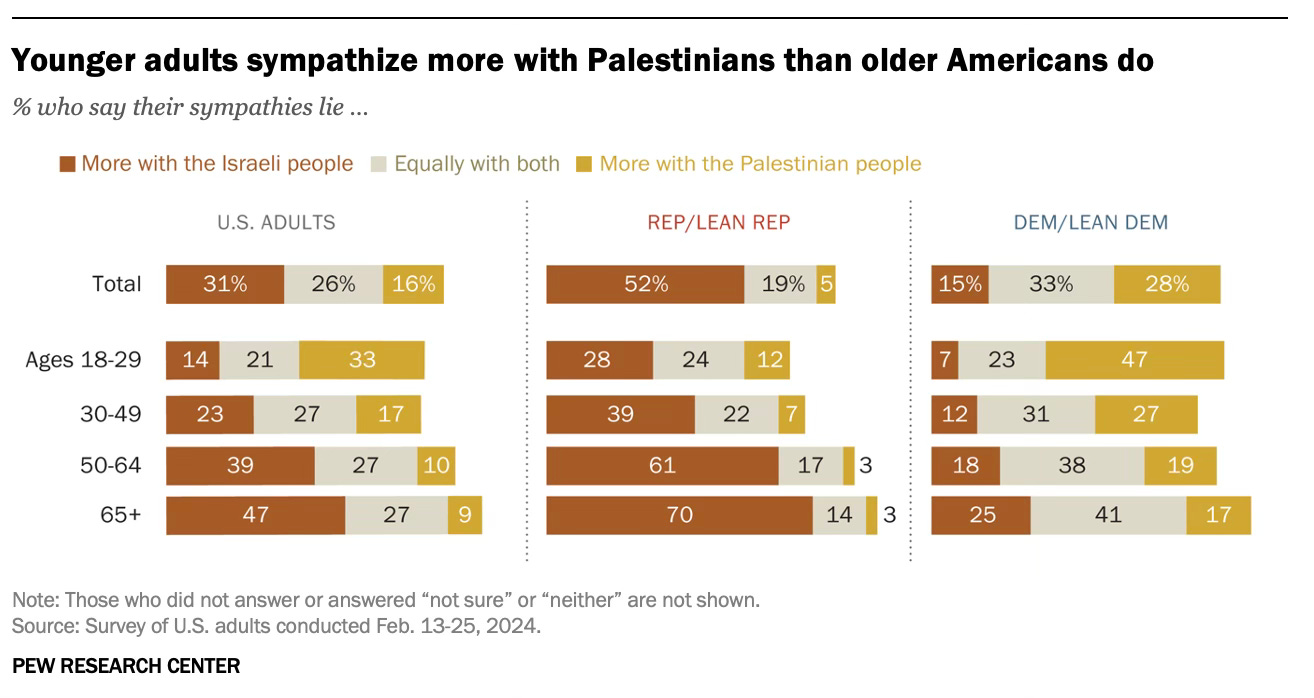

This recent Pew survey is quite telling. There’s an important age effect across party lines, with younger voters tending to be more sympathetic toward Palestinians. But this becomes a major age gap within the Democratic Party specifically, with younger voters siding more with Palestinians than Israelis by a margin of 47 to 7, and older voters siding more with Israelis by a margin of 25 to 17.

From a purely electoral math perspective, Biden — generally a very effective coalition manager — would appear torn within his party, and it’s hard to come up with a baby-splitting approach that would ameliorate both age groups. If he had to pick a side, older voters are far more likely to vote in November. His best bet is for this issue to simply go away, but that doesn’t look likely to happen any time soon.

Meanwhile, on the Republican side, Trump has been critical of Netanyahu, although more for intelligence failures than for the prosecution of the war. Trump is voicing no qualms about Israel’s treatment of Gaza, instead saying:

You’ve got to get it over with, and you have to get back to normalcy. And I’m not sure that I’m loving the way they’re doing it, because you’ve got to have victory. You have to have a victory, and it’s taking a long time.

The implication is that if Trump were president, he would be considerably more acquiescent toward Israel and Netanyahu than Biden and the Democratic leadership currently are.

Now, both Israel’s supporters and critics generally overstate the United States’ leverage over that nation. It’s not zero — Biden’s pressure has likely at least delayed an Israeli invasion of Rafah and allowed some humanitarian assistance in. But Netanyahu is extremely dug into his position and would likely face significant political peril for ending hostilities. (He also faces considerable legal peril if he’s forced from office.)

This brings us back to the particular dilemma of Israel’s critics in the United States. If you have a strong stance on, say, abortion, gun control, climate change mitigation, civil rights, or any of dozens of other crucial issues, one of America’s two major parties likely represents your needs. You might be legitimately cross-pressured on different issues — maybe you support the Black Lives Matter movement but oppose abortion rights — and you have to decide which set of issues is more important to you as an election approaches.

Opponents of U.S. support for Israel have no such option. There’s obviously different rhetoric, and likely very different intentions, from each of the two major parties, but there’s not likely to be drastic change in U.S. policy towards Israel depending on which party is in power.

Now, critics of Israel might well recognize that there are at least some sympathetic elected officials within the Democratic coalition, and they might try agitating to give those officials a greater voice. That’s what primary elections are for. But at the presidential level, there was never that much of a challenge to Biden’s re-nomination, and by the time the Israel-Gaza War emerged as a significant rift in US politics, there was no real time for a new candidacy to emerge.

To the extent the protesters have a realistic political strategy, it’s to force the White House to recognize that they can’t count on young voters to show up for them in November without significant concessions on Israel policy. And given polling trends and the fact that this election was already going to be close, chances are Biden has heard that message loud and clear. That doesn’t mean there’s an obvious way to address it, however.

The parallels between this election year and that of 1968 are really pretty striking. Then, as now, an accomplished but unpopular Democratic administration was facing strong criticism within its own ranks from young protesters. Then, as now, the protesters were frustrated by a bipartisan commitment to U.S. foreign policy – LBJ and his successor, Hubert Humphrey, supported the Vietnam War efforts, and Republicans, if anything, wanted a more aggressive stance. Then, as now, the protesters clearly rankled the political establishment and met with overly zealous police response, and the Democratic National Convention in Chicago will likely be rife with both protest and police. And then, as now, there was a Robert Kennedy in the mix. That doesn’t mean this is all going to end the same way, with the Democrat losing narrowly and the Republican pursuing an even more aggressive foreign policy approach, but it’s at least plausible.

I get the 1968 comparisons but the similarity strikes me as being far more superficial than substantive. The protests are pretty small and tame compared to say 100,000 people marching on the Pentagon or the enormous violence happening in American cities at the time. Likewise Biden didn't face a strong primary challenge at all compared to McCarthy's shocking 2nd place finish in New Hampshire that forced LBJ to drop out. Moreover the comparison of Gaza to Vietnam strike me as being quite a stretch (if not ridiculous to be frank). At the height of the war 250 American servicemen where dying a week from communities across the country. Likewise there was a draft that affected every American with a young male friend or relative. There's nothing like that today.

With regards to Chicago I expect a lot of media coverage of protestors in Millennial Park, and a rather normal convention, nothing like the one in 1968 where it was still unclear who the nominee would be and everyone tuned in to find out.

To be blunt a lot of these comparisons are just Boomer Brain (to use Dave Weigel's term.)

We need to quit sending military aid to Israel. IMHO. Of course, I thought that before October 7th, but even more so now. But I’m voting for Biden no matter what, because I understand the consequences.