When Republicans stopped moderating to win

Both Democratic and Republican senators now pivot rightward when an election is coming

We hear a lot of claims these days about the differences between the two parties, and about how today’s politicians are different from those in the past. But it’s not always that easy to step back and examine this systematically. Yet a look at the behavior of US senators shows that Republicans are now acting very differently from their Democratic colleagues in election years.

One useful way to study electoral pressures is to look at US senators with their staggered terms. That is, a third of the Senate is up for reelection in any given two-year session of Congress, and some previous studies have found that senators facing reelection tend to behave a bit more moderately than those not facing reelection. More specifically, those facing an impending election are more likely to shirk their party and hew to the median voter in their state in an effort to boost their reelection chances.

More recent research by Mike Cowburn and Sean Theriault has found that Republicans, at least, have been changing their approach to elections since the rise of the Tea Party. That is, Republican senators seem to have stopped moderating in election years, and might even be behaving more conservatively to stave off ideological challenges in primary elections.

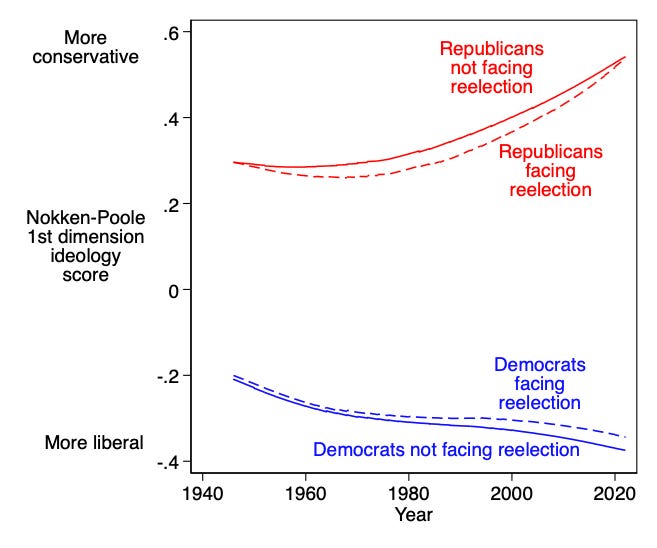

I looked at the roll call voting of US senators of both parties going back to the 1940s. I examine their Nokken-Poole first dimension ideal points, which are estimates of their overall ideological positions based on their voting behavior in the Senate, and these scores can vary from session to session. (These can range roughly from -1, the most liberal position, to +1, the most conservative position.) In the graph below, I divide up senators by their party and by whether they are facing reelection in that cycle. The trend lines shown here are lowess moving averages of all the data points.

The differences across parties are subtle but important. We see both parties moving toward their extremes, although Republicans have done so more rapidly. Also, for Democrats (in blue), we see that those senators facing reelection have behaved more moderately than those not facing reelection, and this gap has grown over time. For Republicans (in red), we see that those facing reelection were substantially more moderate than those not facing reelection for a while, but this difference has been erased over the past decade or so.

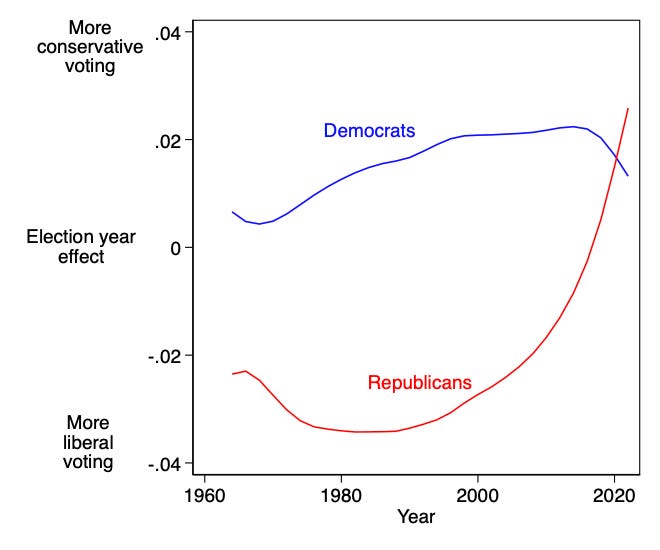

Now, we know that senators’ constituents are hardly the same today that they were in the 2010s, no less the 1960s. So some of the results above could be due to the fact that Republicans are representing very different sorts of voters than Democrats are. To try to sort this out, I ran a regression equation to predict the election-year effect on senators controlling for the vote in their state in the most recent presidential election. The graph below shows the election-year effect by party.

Again, we see a similar pattern. Democrats consistently vote more conservatively in an election year; Republicans did vote more liberally in election years until recently, and now seem to be voting more conservatively. Again, this is not a huge effect — we’re talking about movement of around .02 to .03 points on a scale that theoretically ranges from -1 to +1 — but it is detectable and statistically significant.

This is an important trend and predates the rise of Donald Trump, at least by a few years. The electoral incentives used to be pretty similar across party lines and are now opposites; Democrats believe they should moderate to win, while Republicans believe moderation will shorten their careers.

Now, the precise effect of moderation on reelection chances can be difficult to measure and may not be all that great. And it’s possible Republicans are interpreting it wrong, or at least have over-prioritized primary elections compared to general elections, since at least several candidates are believed to have lost in 2022 precisely because they came off too extreme. But it’s also plausible that both parties are responding rationally to their electoral environments, and Republicans are just more likely to face a serious extremist threat in their primaries than Democrats are.

But importantly, this is leading to very different behavior across party lines. It means different beliefs in accountability, elected officials that keep drifting further to the right of public opinion, and different approaches to recruiting new candidates to run for office. And this helps explain why the obsession with “electability” is a particularly Democratic one.

Thanks to Greg Koger and Mike Cowburn for some feedback and ideas on this piece.

Very interesting data and very sharp analysis. Thanks for this