When populists do foreign policy

What a different GOP, and a different Trump, mean for the world

I am posting this from Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, where I recently attended a symposium hosted by the Emirates Center for Strategic Studies and Research (ECSSR) entitled “Trump 2.0: Redefining Domestic Priorities and Global Strategy.” I was on a pretty impressive panel (see photo above) where we were talking about just what to expect from the next Trump administration and what sorts of effects it would have around the world, including but not limited to the Middle East. Below is a somewhat polished version of my remarks.

As the panel moderator noted, the coalition Trump won office with is a different one than Republicans usually win with — more racially diverse, less college-educated, etc. The Republican coalition has been shifting around for several election cycles now, and what we saw this year was the dominance of a populist faction within the party, a faction that has been there for decades but was often shunted to the side and rarely taken seriously.

This sort of shift has been occurring in conservative parties in many democracies, particularly in Europe, but has really been happening in the US over the past three decades, starting with Pat Buchanan’s presidential campaigns in the 1990s, through the Tea Party movement in the late 2000s, and since 2016 with Trump. These American populist efforts come in different stripes but have several things in common:

a fierce opposition to immigration into the US, especially from the southern border

a conspiratorial world view, seeing a set of “elites” (media, academic, cultural) as steering systems against the needs of “regular Americans” or “average people”

opposition to existing institutions, conventions, and norms, combined with a distrust of expertise and experience

an “America First” orientation, with support for high tariffs to limit foreign trade and promote American industry and manufacturing

This populist viewpoint has existed for some time, but it has generally not been taken seriously. Now it controls a major political party, and that party takes control of the White House and the Congress in one month. This will have several important consequences for U.S. foreign policy.

There are a few ways of thinking about Trump’s interest and power in foreign policy. In one sense, as Dan Drezner notes in his excellent recent column in Foreign Affairs, Trump had little experience or interest in foreign policy when he first became president, and there was an institutional foreign policy apparatus that held a good deal of sway. That’s not the case for this new administration. Trump is bringing his own people in and he has more of a sense of what he wants to do. He’s more inclined to hire and fire staff based on loyalty to his vision. And he has a party that is far more deferential to him than it was in 2017.

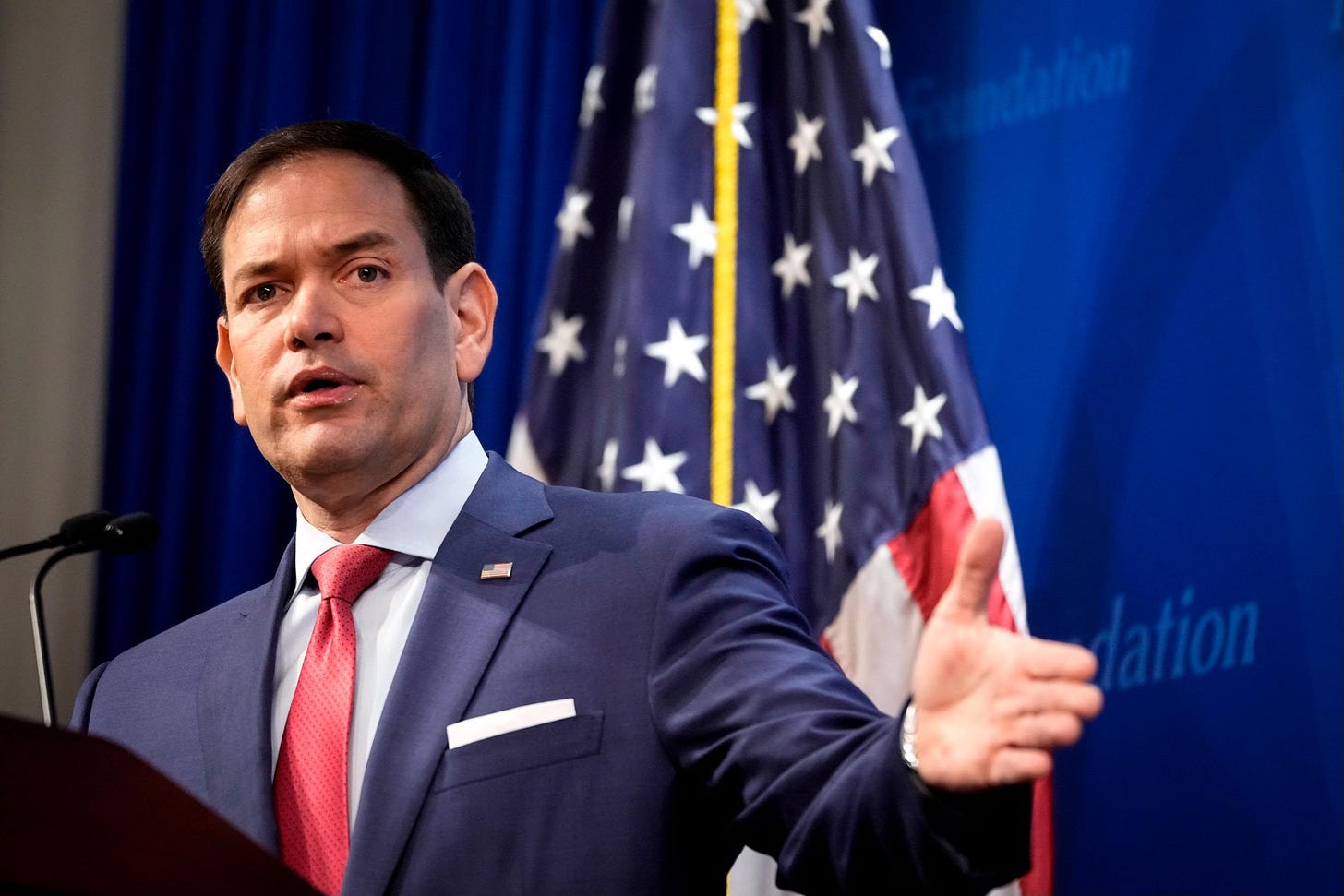

On the other hand, foreign policy is one of the few areas where there is still significant dissent within Republican Party. Secretary of State designee Marco Rubio is a rare figure because he was an established Republican Senator before Trump’s rise and was part of the old Reagan-Bush coalition, advocating an aggressive U.S. foreign policy favoring democracy and open markets. He has changed his stances as his party has, but has remained at least somewhat internationalist, favoring support for Ukraine and Taiwan. Lindsey Graham and a few others behave similarly. Those folks probably won’t openly challenge Trump but they still retain some influence. Rubio is also rare in that he appears qualified for the job he’s been appointed to. What’s more, some of the other State Department appointees have some experience in foreign policy and are not known to be bomb throwers.

Overall, though, we’re going to be seeing some important shifts in policy, including:

a substantial retrenchment of US military commitments, especially with regards to Ukraine.

growing rifts within NATO. I rather doubt the U.S. will withdraw from NATO, but Trump will continue push to undermine coalitions and weaken commitments to this and other such international organizations.

the undermining of many trade agreements, including the USMCA/NAFTA, and the ramping up of tariffs with many nations. Trump will be pushing the U.S. away from its bipartisan post-Cold War consensus on free trade.

a continuation or exacerbation of the trade war with China, keeping tariffs high and quite possibly raising them a great deal.

It’s notable that over the past decade or so, both major parties have become something like anti-war, if not exactly pacifist. There’s just no constituency for a major U.S. military role abroad right now. Partially this is a consequence of President George W. Bush and the War with Iraq / War on Terror. As the public soured on that conflict and it was seen as costing Republicans control of Congress and the presidency in 2006 and 2008, Republicans turned against it, and Democrats portrayed it as the last large example of American hubris. Americans will still support financial support for Ukraine, for Israel to some extent, for Taiwan, and a few other places, but otherwise such appetites are very limited.

Also importantly, while US foreign policy has generally focused on “American exceptionalism,” (the idea that the US is advocating some set of ideals regarding democracy and free markets and not just its own material self interests), this is simply not a priority for Trump. He has openly favored strong men like Hungary’s Viktor Orbán, India’s Narendra Modi, Russia’s Vladimir Putin, and North Korea’s Kim Jong Un.

That said, Trump is not terribly ideological. He has made exceptions to his world view in the past, such as exempting nations he does business with from a travel ban. Nations that win his favor, flatter him, or impress him as being vital to business are likely to get exemptions from some of the most aggressive tariffs and other things. He is highly transactional, and has been willing to work with nations on some issues to get some concessions that are only tenuously related.

Also, my impression is that the Abraham Accords remain something he is very proud of from his first term and wishes to expand on it, inviting other Middle Eastern nations to normalize relations with Israel. This is obviously a challenging environment for that to happen, given Israel’s policies in Gaza and Lebanon. And from what I gathered at this symposium, there is limited interest from other nations in joining. But Trump will likely leverage his close ties with Israel’s governing party to push something along these lines.

It is said that power abhors a vacuum. The U.S. withdrawing from the Middle East and other regions, even if slowly, creates a vacuum. And nations willing to make some investments in promoting business, supporting peace efforts, etc., and have the resources to do it, can expand their influence in this environment.

Seems likely other nations will increasingly bypass dysfunctional America and deal among themselves. That will benefit China, whose Belt and Road program is already extensive.

Seth. Hope you had a good trip back to Colorado and best wishes for a very Merry Christmas….