What did a Trump endorsement mean in 2024?

Some different ways of tracking Trump's probably-inevitable nomination

John Sides has a nice article up at Good Authority about the likely inevitability of Donald Trump’s nomination. As John notes, endorsement patterns showed party “elites” converging on Trump pretty early and resoundingly. Trump received one of the highest percentages of pre-Iowa endorsements of any Republican presidential nominee in the post-1970s era.

And yet I wonder about the value of tracking endorsements in the Republican Party, particularly in the wake of Trump’s nomination in 2016, which he won almost without any elite endorsements. The focus on endorsements suggests a party that follows, to some extent, the wishes of elites; I am not certain that describes the modern GOP.

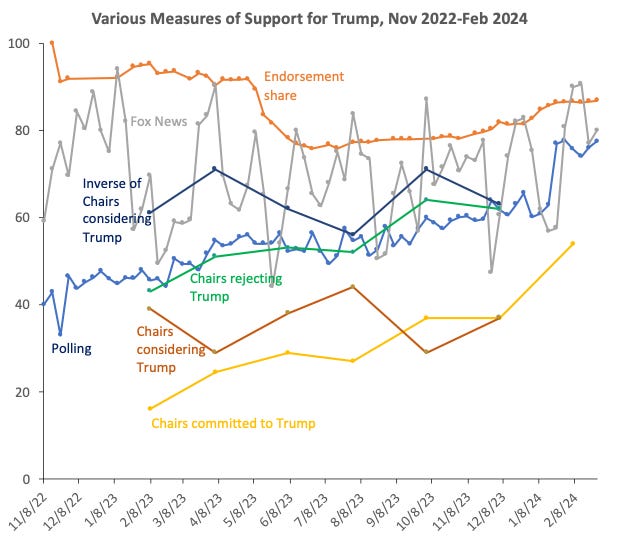

In the figure below, I’ve compiled a number of different measures of things that might steer the Republican Party’s decision. I’ve also included measures derived from my own survey of Republican county party chairs over the past year. I describe all these measures here:

Endorsements: The share of cumulative endorsement “point” counts calculated by FiveThirtyEight that went to Trump for each week.

Polling average: Average poll position of candidates from polls collected from FiveThirtyEight. I only used polling houses with ratings of B- or better.

Fox News: The percentage of mentions of the top eight presidential candidates on Fox News (as calculated by GDELT) that went to Trump each week.

Chairs Committed: In my survey of county chairs, this is the percentage that described themselves as “committed” to Trump.

Chairs Considering: In my survey of county chairs, this is the percentage that said they were “considering” Trump; they could list as many candidates as they wanted.

Chairs who don’t want him: In survey of county chairs, this is the percentage that said they do not want Trump to be the Republican nominee: they could list as many candidates as they wanted.

Inverse of chairs who don’t want him: This is the “chairs who don’t want him” number subtracted from 100. That is, these are the people who don’t say they don’t want Trump.

I’ve charted all these figures from the week of the 2022 midterm elections until the end of February 2024. It’s a is a busy graph, but check it out:

Now, on the basic question of which indicator was a better predictor, that depends what we consider them to be predicting. For what it’s worth, Donald Trump has received about 72% of the votes in the primaries and caucuses so far, and about 91% of the delegates. If we’re going with them predicting the vote, the endorsements, if anything, come in much higher than the vote share. Polling is not bad, although throughout 2023 it substantially understated where Trump would end up. Trump did receive about 70% of the media coverage — which is remarkable considering that he was running against nearly ten other candidates who participated in debates that he didn’t show up to — and that’s actually pretty close to the vote share he won.

An interesting thing about the measures that come from my county chairs survey: a lot of these measures significantly understate Trump’s support within the party. This could well be the result of my drawing a sample of chairs who were less Trump-leaning than party chairs as a whole.

However, one of the most reliable indicators of where the votes would end up going was my last one — the inverse of the percent of chairs who did not want Trump to be the nominee. That is, basically every chair I spoke to who did not say that they did not want Trump to be the nominee ended up backing him. Stated another way, anyone who wasn’t initially outright opposed to him ended up with him. This is a pretty good indicator of the party’s preferences.

But I want to get back to the topic of endorsements. What really strikes me in the graph above is how overwhelming the Trump advantage in endorsements was even in early 2023 and even in late 2022, when there was a broad narrative that Trump was the reason for substantial Republican under-performance in the 2022 midterm elections. That was back when he was polling under 50% and was nearly tied with Ron DeSantis. Party elites were far more bullish on him than the rest of the party.

Which leads one to ask — did the elites lead the voters, or did they stake out a position where they figured the voters were going to end up? And did they pick him because they liked him and thought he would be good for the party and the country, or because they figured they had to back him and would face consequences if they didn’t?

It’s difficult to tease that out of the numbers. My impression here is that backing former President Trump in 2024 is very different from backing, say, George W. Bush in 2000. In the Bush case, party insiders liked what they saw in Bush — he had good name recognition, was trusted by different wings of the party, had a record of accomplishment as governor, seemed like he could win, etc. — but they didn’t feel they had to nominate him. They definitely had other choices, and they wouldn’t have faced primary challengers and death threats for picking someone else.

It’s different with Trump. Quite a few insiders may legitimately like him and look back with fondness on his presidency. But they also likely had the sense that backing someone other than Trump was a fool’s errand, possibly a career-ender, and that party voters would eventually want him whether the elites signaled their approval or not, as happened in 2016.

The 2024 GOP nomination ends up being a pretty good case for the book The Party Decides; that is, it appears that party elites actually decided and the rest of the party followed along. But the dynamic that produced that outcome is substantially different in Trump’s case than it is for most other presidential nominees. In many ways, all that elites may have decided was that they didn’t really have a choice.