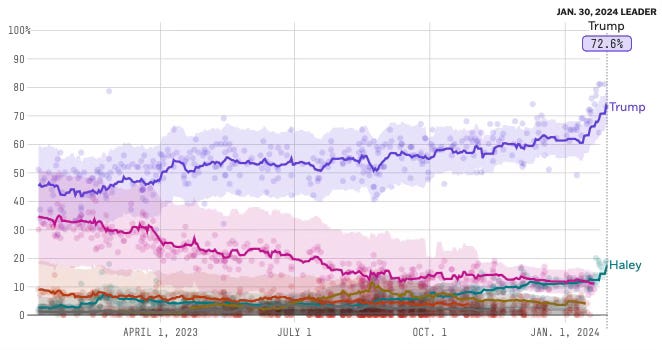

While Donald Trump’s 2024 presidential nomination may well be inevitable, it didn’t look that way a year ago. He was only marginally ahead of Ron DeSantis according to most polls at the time. What really seemed to turn the tide in Trump’s favor, according to a great many measurements and analyses, was being indicted by Manhattan’s District Attorney in early April of 2023. That indictment was associated with nearly a 10-point increase in Trump’s support among Republicans, and a similar drop in support for DeSantis at the same time.

Now, there’s a temptation to say, that’s just part of the weirdness of the modern political era, and Trump specifically. For any other politician, these sorts of things would be politically fatal, right?

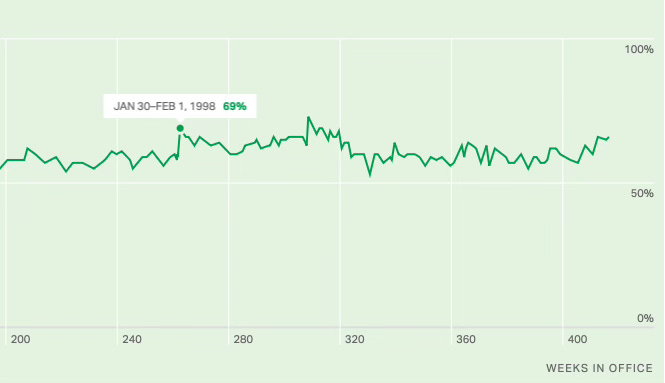

Folks, let me introduce you to Bill Clinton in 1998. It was in mid-January of that year that the Drudge Report published a story about an alleged affair between Clinton and a former intern, Monica Lewinsky. Mainstream press began covering it the following week. On January 26, the White House began its full defense of Clinton, with the President famously declaring “I did not have sex” with Lewinsky. The next day, First Lady Hillary Clinton appeared on the Today Show to warn about a “vast right-wing conspiracy” that had been trying to destroy her husband’s career for years.

Importantly for our purposes here, Bill Clinton’s approval rating, already around 60 percent, went up right around this time, jumping by nearly ten points over its previous average. Those approval ratings remained elevated until the following March, after Clinton was acquitted by the Senate.

Now, there are a number of theories to explain just why a president’s approval ratings would rise during one of the worst stretches of media coverage one could dream up. One is that voters were pushing back against Republican over-reach in pursuing Clinton; they did not approve of his behavior but thought that the hounding of him over an infidelity was excessive.

John Zaller offered a provocative explanation: the scandal forced Americans who were tuned out of politics to start paying attention. When they did, they found that the things that they actually care about when evaluating a president — the economy, the state of war or peace, the incumbent’s overall moderation or extremism — were quite to their liking, and they adjusted their evaluations of Clinton accordingly. It wasn’t that they liked his behavior; they just don’t actually care that much about scandal when it comes to assessing presidential performance.

Another way to think about it, though, might be that it was a rally effect — not a rally around the flag, but around the leader. Democrats saw their leader being attacked (unjustly, in their view), and even those who were skeptical of his leadership felt they needed to stand up and support him at that time.

This is distinct from the sort of rally effect we tend to think of an outburst of patriotism. A classic example of that kind of rally would be right after the 9/11 attacks. Approval ratings of George W. Bush shot up from 51 to 86 percent almost overnight. And importantly, the bulk of this rise came not from Republicans (which went up around 10 points and couldn’t really go much higher) but from Democrats (which went up around 55 points).

By contrast, the bulk of Clinton’s rally in 1998 came from Democrats. Clinton did see some rise among Republicans but it was very short-lived.

Okay, back to Trump. My impression is that Republicans interpreted the first Trump indictments much the way Democrats interpreted the Clinton impeachment drive — an unjust attack on their leader. At that point, even Republicans who were not particularly enthusiastic about Trump, including some who were already supporting DeSantis, rallied behind their party’s standard bearer.

As Julia Azari notes, this is part and parcel of an era where the party has come to be fixated almost exclusively on the presidency. All party resources or mobilized to defend the president. This is also related to Trump being seen as the Republican party’s leader, and even, in some ways, their incumbent.

But there are a few key lessons we can learn from both the Clinton and Trump episodes. One is that large scandals are not axiomatically fatal for a political career. If a politician chooses to weather the storm rather than resign, they might well survive it. Another lesson is that the sort of up-is-down feeling about the Trump era, where getting in trouble is actually good for a candidate, is not unique to this era or to just Trump.

You leave out the fact that the Clinton affair was represented correctly while now even middle of the road media leave out the worst part of Trump's behavior in fear of losing subscriptions.

To me this is a significant difference that may explain why rather unpolitical citizens tuning in chose Clinton's side while now similar people are misled into following Trump.

And DoJ is helping Trump's narrative by pretty much ignoring his crimes and his accomplices.