They were always going to get to this decision - the question was how

Some reflections on the strained logic of Trump v. Anderson

Shortly after the US Supreme Court agreed to take up the case of Donald Trump’s ballot disqualification late last year, Harvard law professor Nick Stephanopoulos predicted:

I expect the court to take advantage of one of the many available routes to avoid holding that Trump is an insurrectionist who therefore can’t be president again.

And yeah, that was the right call. And in the end, they came up with a rough framework that basically all the justices could agree on: that a state is free to disqualify candidates for state office as it sees fit but not candidates for national office, since that affects other states; only Congress has this power. The majority then went on to say more things about congressional power and candidate immunity that were clearly more than all the justices were comfortable with, as some subtly barbed concurring statements by Justices Barrett, Sotomayor, Kagan, and Jackson suggested.

However, they all seemed basically on board with the idea that there must not be a “patchwork” of different candidates and election systems throughout the country:

The “patchwork” that would likely result from state enforcement would “sever the direct link that the Framers found so critical between the National Government and the people of the United States” as a whole. But in a Presidential election “the impact of the votes cast in each State is affected by the votes cast” -- or, in this case, the votes not allowed to be cast — ”for the various candidates in other States.” An evolving electoral map could dramatically change the behavior of voters, parties, and States across the country, in different ways and at different times…. Nothing in the Constitution requires that we endure such chaos—arriving at any time or different times, up to and perhaps beyond the Inauguration.

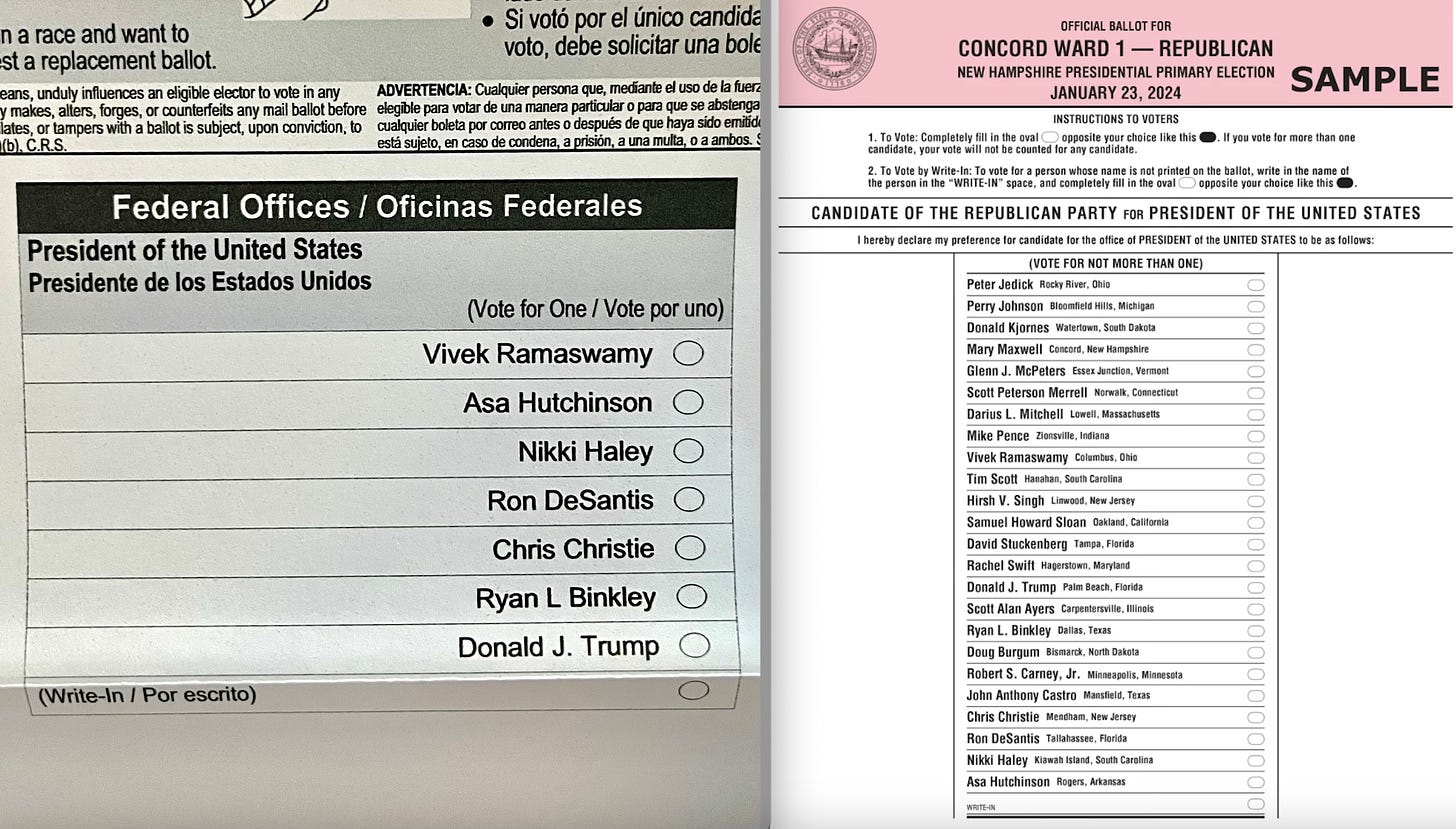

Yes, that would be a problem if there were such chaos, like… Well, let’s take a look at the Republican primary ballots in Colorado and New Hampshire:

So one state having 7 candidates and one state having more than three times as many seems like one of those patchwork things that are supposed to be a problem. Can candidates like Perry Johnson now use this decision as the basis for a lawsuit claiming they deserve to be on every state primary ballot?

The simple fact is that we really do not have nationwide election administration. If I want to run for president, there is no office in Washington, DC for me to file my forms and pay a fee; this is all handled by 51 secretaries of states and their equivalents. There are some areas where the federal government is involved; the FEC, for example, records campaign expenditures and donations and has modest ability to punish legal violations. But for the most part, we have state-level administration of nationwide elections, and the Court knows that.

Now, if the Court wants to mandate nationwide administration for elections, that would be awesome. It would allow us to address various inequalities that exist across states in terms of funding, election machinery, ability to vote, voter registration, ballot access, counting processes, and more. But the Supreme Court is clearly not for this, outside of this particular case. Indeed, it’s been just a decade since the Shelby decision in which the Court invalidated part of the Voting Rights Act, which was congressional intervention in elections designed to remedy racial inequalities in voting access and had been reauthorized by Congress just six years earlier.

Every one of [the justices] decided, as transparently as possible in this case, that the text of the Constitution would have forced them to do something they did not want to do or did not think was a good idea, and so they would not do it. The justices did not want to throw Trump off the ballot, and so they didn’t. Not only that, but in order to head off the unlikely scenario of Congress trying to disqualify Trump after the election, they said that Congress must specifically disqualify individual insurrectionists, despite such a requirement having no basis in the text. Even if you agree with the majority that this was a wise decision politically, it cannot be justified as an “originalist” one; it was invented out of whole cloth.

They got to the decision they wanted, which involves the Court not looking like it’s interfering in the election. This is consistent with a pattern in a lot of the judicial system, which has been fairly aggressive in pursuing participants in the January 6th insurrection but far less so in pursing its organizer. And in fairness, this is more than just an optics issue — the perception of the justice system removing the sitting President’s main political rival does indeed go to the heart of a branch that relies greatly on public legitimacy. The problem, of course, is that a judicial system that goes out of its way not to hold someone accountable who committed an insurrection in full public view is that that can damage the system’s legitimacy just as much, if not more. And it makes the next insurrection all the likelier.