There's no ideal number of candidates

It's possible to organize against a popular frontrunner, but that doesn't mean Republicans will

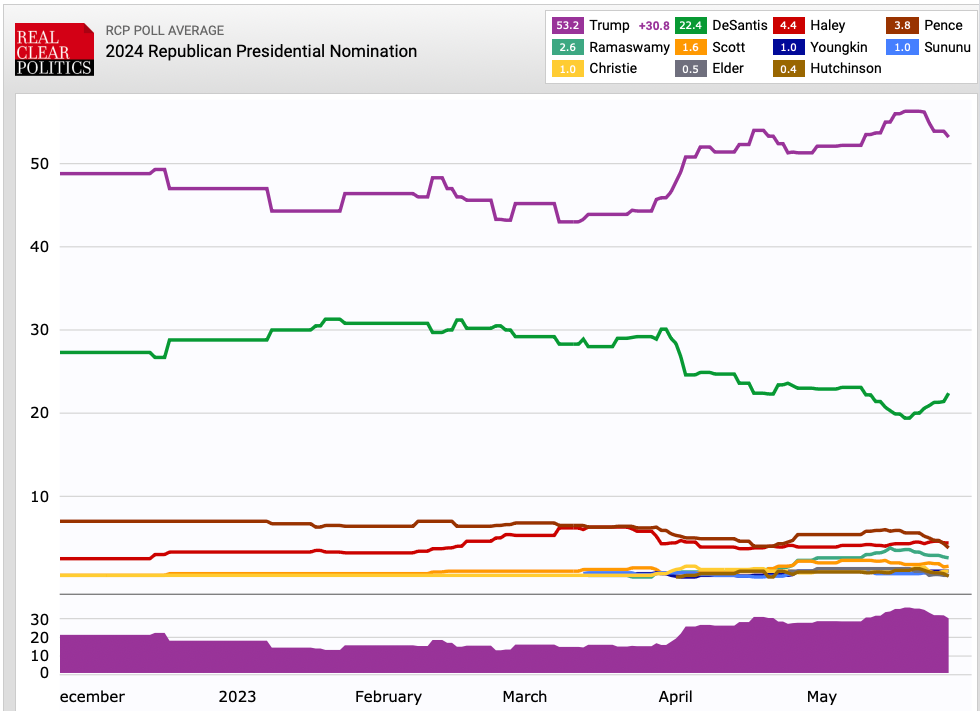

This is beginning to look like yet another crowded presidential election cycle. More people continue to throw their name in for the Republican presidential nomination, and depending how you define things, there are 15 to 20 people currently running, which is similar to what the Republican field looked like in 2016 (and almost what the Democratic field looked like in 2020).

However, quite a few writers and pundits in these recent pieces at Politico and the New York Times seem convinced that the large number of candidates assures Trump the nomination. For example:

The Bulwark’s Sarah Longwell: “For those of us who view Donald Trump as an existential threat, we’re kind of tearing our hair out over this idea of a crowded field and a repeat of the same dynamics in 2016.”

New Hampshire House Majority Leader Jason Osborne: “If those people are all still in the race when January comes around, it’s going to be 2016 all over again, and Trump will win. That’s just how it is.”

Republican strategist Dave Carney: “It’s a gigantic problem. Whatever percentage they get makes it difficult for the second-place guy to win because there’s just not the available vote.”

I’m not really buying this. Three candidates can split up a field just as easily as thirteen can.

But just to play out the scenario, let’s imagine that it’s a few weeks before the 2024 Iowa caucuses, Donald Trump has around 40% polling support among Republican voters and caucus goers, and DeSantis is at 35, with Nikki Haley, Tim Scott, and Mike Pence at 5 each. Yes, DeSantis could win the nomination if those other three candidates dropped out and nearly all their votes went his way (two big ifs). But what if you had ten other candidates in there with one percent support each? That… wouldn’t make much of a difference.

Yes, it matters if a lot of candidates each have 5 to 10 percent of the vote, but that doesn’t tend to be how these things play out. You tend to see three or four candidates with the bulk of the vote, and the rest hovering just above zero. (At the beginning of January 2016, only four of the 17-ish Republican presidential candidates had above 5 percent. At the beginning of January 2020, only four of the 20-ish Democratic presidential candidates had above 5 percent.)

What’s far more important than the number of candidates is the ability of the party to actually winnow the field.

The telling example is the Democrats in February of 2020. Again, it was a very large field, but there were only a handful of candidates splitting the non-Bernie Sanders vote. Biden, who had enjoyed a comfortable lead in polling (and endorsements and other forms of support) throughout 2019, saw his support crater after losses in Iowa and New Hampshire, with Buttigieg, Klobuchar, Warren, and Bloomberg benefitting.

And for a little while, the Democratic establishment was truly panicking, convinced that the nomination was going to go to Sanders, whom they were convinced a) was hostile to them, and b) would lose to Trump. And that’s when a range of party actors, from Jim Clyburn to Terry McAuliffe to Jimmy Carter, started pressuring some of the other candidates to drop out and endorse Biden. Buttigieg and Klobuchar did so right after South Carolina, and Warren and Bloomberg followed suit right after Super Tuesday. Sanders’ support didn’t crater after that, but Biden’s skyrocketed with the lack of other real alternatives.

As Julia Azari notes, there was something of a telling example in the Democrats of 2008. A lot of the party had converged behind Hillary Clinton, but not all — she was hovering at around 40-45% of support in late 2007. It was a fairly large field for the time — roughly ten candidates — but only three with any real level of backing. But some in the party were uncomfortable with her as the nominee, due in part to a) her vote to authorize the Iraq War, and b) a concern that she couldn’t win in November. She was ultimately denied the nomination after a number of prominent Democrats endorsed an alternative, Barack Obama, and Obama allayed some fears about his inexperience with an impressive victory in the Iowa caucuses.

If Trump is denied the Republican nomination, it would likely look something like the Clinton example from 2008, with prominent party leaders rallying around a clear alternative and pressuring others to drop out and endorse that alternative. That job is pretty clear and it doesn’t change a lot with more single-digit candidates in the race. The real question is whether Republicans have the capability of and interest in organizing against Trump. They didn’t in 2016, which is why Trump ended up as the nominee. The evidence so far doesn’t suggest things have changed that much, but they know what they need to do if they want to do it.