The real story is the nomination, not the general election

Trump benefited from a national tide, again

To my mind, there’s actually not a ton to explain about the November 2024 presidential election. As happened in democracies around the world over the past year, the majority party got blamed for inflation and other economic problems and lost vote share because of it. Trump has now run for president three times, all in anti-incumbent environments. He won the two times that that environment was on his side, and he lost the one time he was an incumbent. We can talk about the candidates’ stances on Gaza or debate performances or ad expenditures or anything else until we’re blue in the face, but it still comes back to this basic point that the identity of the candidates probably didn’t matter all that much.

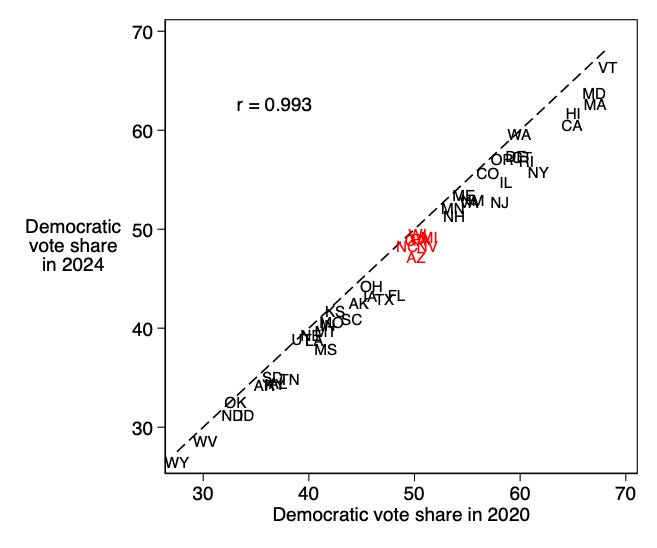

Here’s another way to look at it graphically. The scatterplot below shows the state-level presidential election results in 2020 and in 2024. Swing states are labeled in red. Granted, some of the results are still being tabulated, but what we’re looking at here is a nationwide intercept shift. It wasn’t about where the campaign was being waged or how smart the ads were or anything else — the country, like pretty much every other country that’s had an election recently, turned against the incumbent part by a few points.

To me, the interesting part is how Trump came to be the Republican nominee to benefit from this tide. (Yes, as someone who is focused on party nominations and writing a book about the 2024 GOP nomination, I am self-interested here.)

Think about where Trump was two years ago. He was still unpopular from the January 6th insurrection and had been kicked off of Twitter. Republicans had just broadly under-performed in the 2022 midterm elections and Trump was being largely blamed for that, both for recruiting poor candidates and for making himself the main topic of campaign conversation. Polls showed him only slightly ahead of Ron DeSantis for the presidential nomination. A year later, he basically had the nomination sewn up without having participated in a single debate. A year after that, he’s picking his cabinet.

That’s an important story, and the story I’m trying to tell in my forthcoming book. In many ways, it’s a similar story to what happened in 2015-16 — a substantial chunk of active Republican voters very enthusiastically and unabashedly loved him, and others leaned toward him and were just looking for some sort of rationale to justify backing him. The string of indictments against Trump provided that rationale (He’s being unjustly attacked and deserves my support), but my guess is those Republican voters would have gotten there anyway, using some other pretext.

The big difference from 2015-16 is that Republican elites could actually see this coming in 2023-24. They’d seen the movie before; they knew they had little chance of derailing Trump’s nomination, and if they tried and failed he could end their career with a single endorsement in the next primary. So they rallied behind him early instead. All the other Republicans running for president were essentially running for a situation in which Trump was dead or in prison; as long as he was able to put together a campaign, there was no way they could deprive him of the nomination.

I am inclined to agree with Jonathan Bernstein that the general elections of 2016, 2020, and 2024 were “really normal elections with a really abnormal candidate.” That is, Trump is an unusual nomination candidate who runs like no one else can run, and he behaves in office likely pretty much no one else behaves. This week’s cabinet announcements are a great example of this. But in the general elections, he benefits from or is hurt by the same political fundamentals that affect anyone else with an R next to their name.

Now, there’s one aspect of 2024 that stands apart from what I’ve argued above — abortion. As many commentators have noted, abortion rights initiatives did well in these elections but largely didn’t help Kamala Harris. And that stands apart from the more local elections of 2022 and 2023, where the boost in pro-choice turnout definitely aided Democratic candidates. Voters don’t do a ton of research but surely saw Harris as the candidate more supportive of abortion rights. And any idea that voters drew a distinction between the candidate and her party’s stances kind of runs counter to the picture I’ve drawn above, where the candidates rise and fall based on public perceptions of the parties. At any rate, I’m still thinking this through, but I’ve yet to read a convincing analysis of just what happened there.

The axiom that victory has a thousand fathers has an oft-unnoticed corollary: defeat has a thousand deadbeat dads. To an anti-incumbent-governing-party cycle, we can add indeterminate (maybe indeterminable) quantities of misogynoir, forgetful voters, low/no-informatuon voters, complacent voters, epistemically closed voters, manospehere influencers, social-media deployment of disinformation campaigns from Trump's domestic and foreign allies, the safety-valve of abortion referenda that probably allowed some state-speciric ticket-splitting, etc. etc., on to infinity. The heartening sign for me is that, in five of the six swing states in which there were significant statewide down ballot races (PA, NC, MI, WI, NV, AND AZ), Ds performed well. They won four vigorously contested Senate seats (AZ, MI, NV, and WI) and control of all statewide offices in NC.

As of today there are still ~ 7M fewer voters in the presidential race than in 2020. To me, that is confounding. We need to know what these folks decided to do (or not do) and why they did/didn't do it. (Not including, of course, Biden and Trump voters who passed away since 2020.)

Seth, congratulations on the book deal. Now the question is: are you going to post chapters of the book here as they are written (we don’t need the edited final version for publication to get the thrust of your findings)?