The "better training" dodge

ICE's problem is incentives, not skills

Essentially all Democrats in office, along with more than a few Republicans, have come around to the idea that ICE must be reformed in the wake of the killings of Renée Good and Alex Pretti. “Reform,” of course, can mean a lot of different things, but one area people seem to be settling on is better training. Agents, that is, should receive training much longer than the existing 47-day mandate, and they should know how (and more importantly, when) to employ lethal force. My impression is that the call for better training is a dodge and wouldn’t actually help all that much.

Possibly the best piece of evidence in my favor is that those who killed Good and Pretti were experienced and well trained. The agents who shot Pretti in the back were Border Patrol agent Jesus Ochoa and Customs and Border Protection officer Raymundo Gutierrez, who had been with their agencies since 2018 and 2014, respectively. Jonathan Ross, the ICE agent who gunned down Good in her car, was an Iraq War veteran and served in the Indiana National Guard for six years. He’s been with ICE since 2016, and, on top of all that, is a firearms instructor. It’s hard to see how better training would have prevented either of these brutal killings.

What is likely far more important than training is incentives. If officers will pay a steep price for killing unarmed civilians, they’ll try hard to avoid it. If they’ll pay no price for it, and indeed be rewarded for their brutality, that’s what you’ll get, no matter how well trained they are.

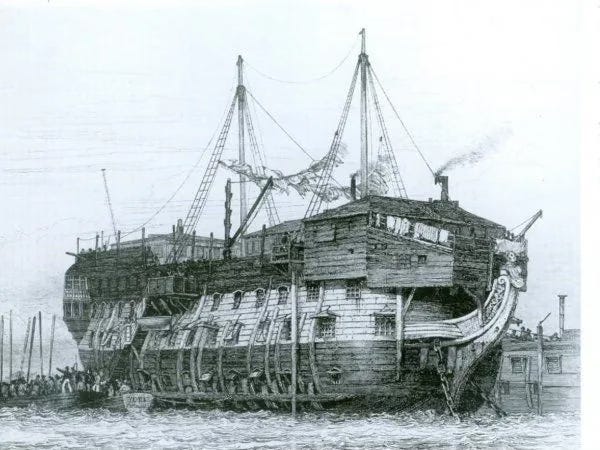

A related parable is that of the English sea captains hired to transport prisoners to Australia in the late 1700s. It was a deadly journey, with many prisoners dying in transit due to disease, malnutrition, and a lack of medical care. An estimated 12% of such prisoners died between 1790 and 1792. English society was repulsed by these accounts and leaders proposed all sort of solutions — better moral training for the captains, more education, paying captains better, shaming them into caring for prisoners, etc. — none of which worked.

The problem was not the captains. The problem was the incentives. They were being paid for every prisoner who boarded their ships. In 1793, the government began paying captains more for every prisoner who arrived safely. Mortality dropped to nearly 0%.

Flash forward to today. As Atlantic journalist Caitlin Dickerson reports (via an interview with Ezra Klein), incentives for ICE agents have shifted a great deal since Trump returned to power in 2025 and put Stephen Miller in charge of immigration policy. Previously,

you would always fear discharging your weapon in an interaction, even a potentially violent and dangerous one. Usually the concern was that officers would be too unwilling to use their gun because they worried about potential repercussions…. And now it’s almost as if the opposite fear is true. We’ve seen in ICE people losing their jobs, high-level officials losing their jobs because they’re not delivering enough deportations, they’re not being aggressive enough…. The only thing you will get in trouble for is not being aggressive enough.

As Miller and the Department of Homeland Security declared last month in a post to “all ICE officers”:

You have federal immunity in the conduct of your duties. Anybody who lays a hand on you or tries to stop you or tries to obstruct you is committing a felony. You have immunity to perform your duties, and no one—no city official, no state official, no illegal alien, no leftist agitator or domestic insurrectionist—can prevent you from fulfilling your legal obligations and duties.

Look, with ICE or with any department of government that can legally take a life, obviously some level of training matters. You want agents to understand how to handle a weapon, how to resolve a violent situation, etc.

But ICE didn’t get so deadly so quickly because they weren’t trained well. If you want fewer deaths, stop rewarding them for killing people.

Exactly. We don't need better training. We need meaningful consequences, and even tougher, meaningful consequences we're not relying on a member of this administration acting to enforce.

As Heather Cox Richardson has written, what happened in the concentration camps would not have been ameliorated by better training.