Republicans in the 1960s faced a choice over the future of their party that would determine the future of the nation. They needed to build a majority and had to decide where to go to find those votes. Should they try to win over newly enfranchised Black voters in the wake of voting rights laws? Or should they try to win over southern whites — longstanding Democrats for historical reasons, but increasingly uncomfortable with that party as it embraced civil rights? Kevin Phillips, who passed away recently at the age of 82, was one of the most influential analysts pushing Republicans in the latter direction. His writings continue to have an enormous impact today on the way Americans live, vote, and fight.

Much of this started as a debate among Republican over just why Richard Nixon had lost to John Kennedy in 1960. Was it for failing to reach out to Black voters (notably, and very visibly, Nixon did not contact Coretta Scott King upon her husband’s arrest, while JFK did)? Or was it for failing to stand up for conservative principles? For a while, Republicans seemed to be reaching out to both constituencies at the same time.

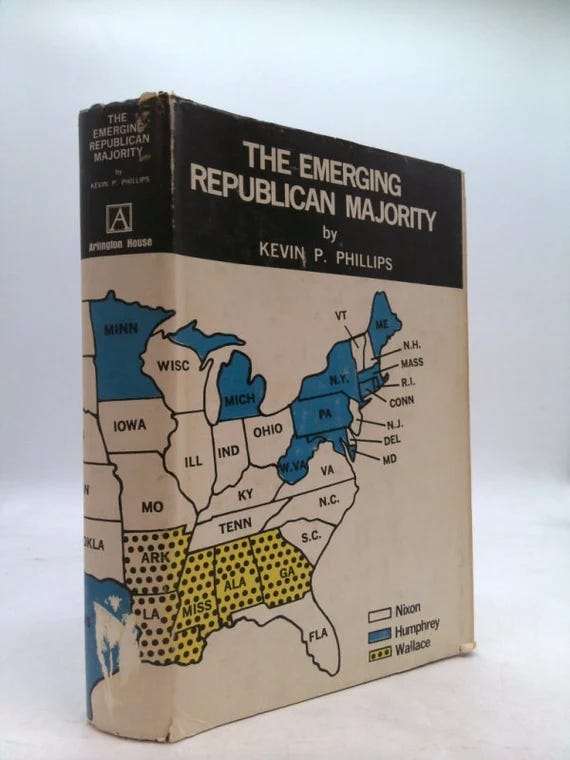

This conversation reached new urgency after Nixon’s very narrow win in 1968. Was there some way to ensure Republican victories in the future without having to rely on the chaos that defined 1968? Phillips seemed to think so. In his famous The Emerging Republican Majority (1969), Phillips declared that the key was going after the 14% of the electorate that voted for former Alabama Governor George Wallace. This vote, he surmised, was not a fluke, but rather a signal of a large chunk of the white electorate declaring its independence from the Democratic Party and its openness to the GOP. This “southern strategy” would end the era of Democratic dominance and pave the way for a Republican future, in Phillips’ view.

As Geoffrey Kabaservice wrote in his book Rule and Ruin,

It was Phillips’ thesis that the Republicans could build an enduring majority by corralling voters troubled by “the Negro Problem” and drawing in elements that had not traditionally been part of the Republican Party: conservatives from the South and West, an area for which Phillips coined the term “the Sunbelt.” He believed that the Democrats’ downfall was decreed when liberals shifted their support from programs that taxed the few on behalf of the many, as in the New Deal, to programs that taxed the many on behalf of the few, as in the Great Society. The few who benefited from these programs, in Phillips’ view, were mainly African-Americans: “The principle force which broke up the Democratic (New Deal) coalition is the Negro socio-economic revolution.”

In a famous interview with Garry Wills, Phillips remarked, “White Democrats will desert their party in droves the minute it becomes a black party. When white southerners move, they move fast.” To this he added that the secret of politics is “knowing who hates who.”

The Nixon administration largely embraced Phillips’ ideas. Nixon’s whole approach of courting white ethnics, of campaigning on “law and order” as George Wallace did, of reaching out to white country musicians like Merle Haggard, of playing up to working class whites in the Hardhat Riots, and more was to speak to the disaffected whites rather than the newly enfranchised Blacks. (And as Kevin Kruse notes, there were plenty of competing viewpoints within Nixon’s circle. This path was a choice.)

In matters of shifting partisan loyalties, it can be difficult to know just how much of it is intentional, as opposed to just the natural ebb and flow of voter coalitions and preferences. The fact that racially conservative southern whites were still regularly voting Democratic 100 years after the Civil War was already a remarkable feat on its own; it seems unsustainable, but it had already been sustained for more than half the nation’s life. Whites’ departure from the Democratic coalition might well have happened just as a consequence of the Voting Rights Act. It’s not clear whether it needed the additional push from writers like Phillips and leaders like Nixon.

But to the extent it did, these people probably had a greater role in the ensuing half century of polarization than anyone else. It was the moving of white conservatives from the Democratic to the Republican Party that lay at the heart of party polarization; the reason there used to be liberals and conservatives in both parties and really aren’t today stems from those decisions that were made in the 1960s and 70s. Looking at Phillips’ work helps us see not only the source of this polarization, but also the fact that race is at the heart of it.

Recently over at his place Yglesias outlined his idea for a TV show called "TRICKY" where Nixon wins in 60's and ends up going to the other way and courts the black vote in the run up to 1964 (he also imagines Nixon pushing for a moonshot and the US getting bogged down in a guerilla war in Cuba after Nixon invades in the aftermath of the failed Bay of Pigs fiasco). Think Mad Men meets For All Mankind meets Oliver Stone's movie Nixon.

I'd watch the hell out of that (especially if they have Bryan Cranston as LBJ in the Senate plotting to tear Nixon down).