I’m in the middle of teaching a class on the politics of the 1970s, so pardon if this seems a bit off topic. But I wanted to talk a bit about a particularly high-leverage loss for Democrats — George McGovern’s loss to Richard Nixon in 1972. This loss was particularly crushing to idealistic young Baby Boomers and helped to shape how the Democratic Party would behave in the coming half century.

The 1970s have a reputation for being a rather cynical decade. The network programmer portrayed by Faye Dunaway in “Network” (1976) summed up the atmosphere well: “The American people are turning sullen. They've been clobbered on all sides by Vietnam, Watergate, the inflation, the depression; they’ve turned off, shot up, and they’ve fucked themselves limp, and nothing helps.”

No, it wasn’t a completely cynical decade. It produced moments of gorgeous idealism like “Free To Be You And Me,” the alien greetings on the Voyager probes, Helen Reddy songs, and more. But for the most part, it was a time of reassessing the failed idealistic and revolutionary spirit of the 1960s. As Hunter Thompson described the 60s in 1971:

We had all the momentum; we were riding the crest of a high and beautiful wave. So now, less than five years later, you can go up on a steep hill in Las Vegas and look West, and with the right kind of eyes you can almost see the high-water mark—that place where the wave finally broke and rolled back.

One of the inadvertent expressions of the revolutionary spirit of the 1960s was the reforms to the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination process. 1968 was a profoundly awful year for a number of reasons, not the least of which was the political engagement of many young idealistic Democrats who sought to make Bobby Kennedy their standard bearer, only to see him gunned down, and then to watch party leaders nominate a pro-war Hubert Humphrey while Chicago police beat war protesters around the convention center mercilessly. The post-election reforms were initially dismissed by most party insiders, until they discovered they actually weren’t in charge of presidential nominations anymore, and many of them were no longer even convention delegates.

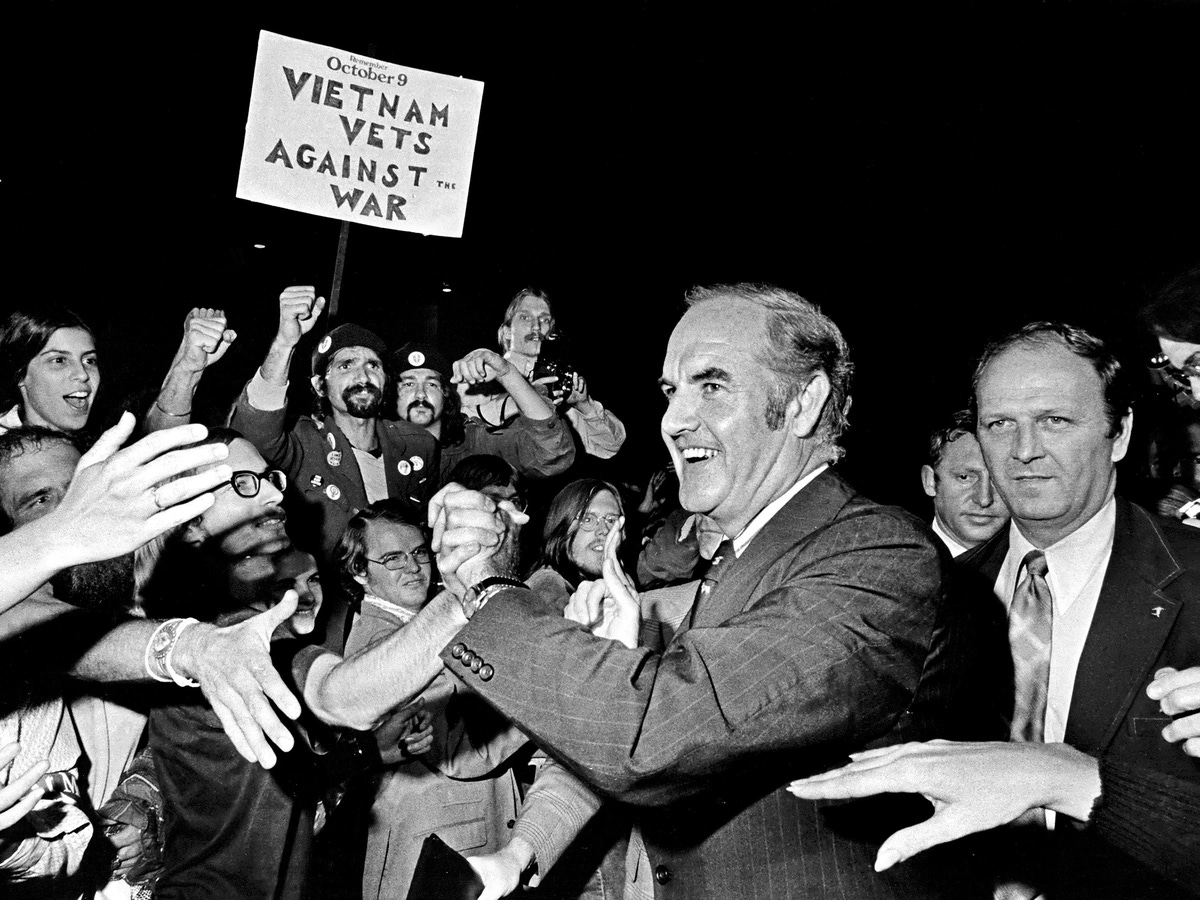

Those reforms opened up the 1972 Democratic convention in Miami to many new faces; the post-1968 reforms had created rules allowing an influx of women, young people, and people of color to state delegations. And many delegates were now pledged to presidential candidates and selected in primary elections; party leaders had a far harder time steering the nomination in directions they wanted.

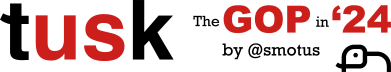

Sen. George McGovern of South Dakota figured this system out earlier than most other candidates. He campaigned early and heavily in the primaries in New Hampshire and Wisconsin and other media-dominated contests, recognizing that such contests now had a great deal of leverage over picking nominees. Many young first-time voters began volunteering for his campaign and proved unexpectedly energetic and disciplined in securing him the nomination.

McGovern’s candidacy was one of the most hopeful and optimistic presidential campaigns in the history of the Democratic Party. He spoke of ending the Vietnam War, of granting amnesty to those who’d dodged the draft, of creating a guaranteed minimum income program, of abolishing racism and sexism, and more, and he welcomed idealistic young people into the campaign. The people who’d been so disillusioned by the end of the 60s suddenly had something to believe in again — Hunter Thompson described it as a 1960s campaign in the 1970s. And perhaps more importantly, these young people got their presidential nominee over the wishes of the party establishment. Party elders didn’t want the McGovern insurgency; his idealistic volunteers won it anyway. Imagine the most die-hard Bernie Sanders fan you know, and then what that person would be like if Sanders had actually gotten the nomination over Hillary Clinton or Joe Biden.

And then — and this is the most important part — McGovern got absolutely crushed in November. Nixon beat him by 23 percentage points in the popular vote, winning every state except Massachusetts and the District of Columbia. It is difficult to overstate what a brutal loss that was for young idealists who had gotten the nominee they wanted only to experience one of the most lopsided presidential elections in history. Quite a few of those young people are still working in Democratic politics today, and they haven’t forgotten that early lesson.

My impression is that many Democrats are still haunted by this loss. Indeed, in February of 2020, when Joe Biden’s campaign looked to be cratering post-New Hampshire and a Sanders nomination briefly looked like a real possibility, the name on many political observers’ lips was George McGovern. “Bernie Sanders is George McGovern,” wrote Derek Thompson. A McGovern volunteer urged his fellow Democrats not to nominate Sanders, lest they repeat the 1972 debacle. Others wrote extensively about the dangers Sanders presented, based on the McGovern model.

The 1990s book and film of Primary Colors contain a memorable scene where Jack and Susan Stanton (the Bill and Hillary Clinton stand-ins) are confronted by their longtime friend Libby Holden about their betrayal of idealism. Libby says she learned about idealism from them in 1972. She had wanted to do the same dirty tricks to Nixon that Nixon was doing to Democratic candidates:

Libby: “I said… we gotta be able to do dirt too. And you said no — our job is to end all that. Our job is to make it clean, because if it’s clean, we win, because our ideas are better. You remember that Jack?”

Jack: “That was a long time ago.”

Susan: “Libby, you said it yourself. We were young. We didn’t know how the world worked. Now we know.”

Democrats pivoted hard away from McGovern following that election. Following Carter’s presidency, Democrats made further reforms to make it less likely an insurgent candidate would become the presidential nominee, and arguably none has since. (Barack Obama’s 2008 campaign is a possible counter-example, although he was hardly a radical pivot from party orthodoxy.) Republicans went a decidedly different route in 2016, but they also didn’t have the specter of a McGovern-style loss hanging over them.

A McGovern-style loss almost certainly couldn’t happen in today’s political system. For one thing, voters are just far more loyal to one party or the other than they were back then. Many traditionally Democratic-leaning labor unions either refused to back McGovern or actually endorsed Nixon that year; that just wouldn’t happen now. And besides, McGovern’s negative impact on the Democratic vote is almost certainly over-hyped. Nixon was heading to a pretty solid reelection anyway; the 1972 economy was actually growing at a pretty good clip. Nixon had ended the draft and the war was winding down; the war protests that had splintered society had become far less prevalent by 1972. The Watergate investigations were mostly a minor local news story at this point. These were conditions under which incumbents tend to get reelected. A different Democratic nominee probably would have done better, but still not come close to winning.

Today, there are probably still some candidate effects, but they’re far reduced. Sanders might well have done worse in the general election than Biden did, but not by a lot. But the specter of such a loss still hangs heavy half a century later. Even as Republicans tear themselves apart this year over their ideological purity, Democrats refuse to be caught being too idealistic.

It seems unfair to put McGovern's loss alone as why Democrats are afraid - the repeated failure of UK Labour to win elections when they ran similar campaigns is more evidence that this was a genuine and on-going electoral danger. UK Labour's election losses 1979 and 1983 and then under Corbyn all provided follow-on evidence for the McGovern hypothesis. I realize there are good responses for how none of either UK or US electoral results proves the McGovern Hypothesis (tm), but that doesn't prevent a pretty good argument being put together.